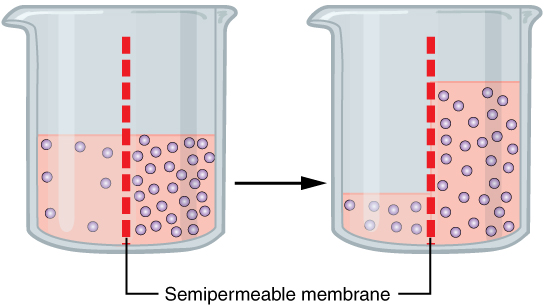

Osmosis (/ɒzˈmoʊ.sɪs/)[1] is the spontaneous net movement of solvent molecules through a selectively permeable membrane into a region of

higher solute concentration, in the direction that tends to equalize the solute concentrations on the two sides.[2][3][4] It may also be used to describe a physical process in which any solvent moves across a selectively permeable membrane (permeable to the solvent, but not the solute) separating two solutions of different concentrations.[5][6] Osmosis can be made to do work.[7] Osmotic pressure is defined as the external pressure required to be applied so that there is no net movement of solvent across the membrane. Osmotic pressure is a colligative property, meaning that the osmotic pressure depends on the molar concentration of the solute but not on its identity.

Osmosis is a vital process in biological systems, as biological membranes are semipermeable. In general, these membranes are impermeable to large and polar molecules, such as ions, proteins, and polysaccharides, while being permeable to non-polar or hydrophobic molecules like lipids as well as to small molecules like oxygen, carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and nitric oxide. Permeability depends on solubility, charge, or chemistry, as well as solute size. Water molecules travel through the plasma membrane, tonoplast membrane (vacuole) or protoplast by diffusing across the phospholipid bilayer via aquaporins (small transmembrane proteins similar to those responsible for facilitated diffusion and ion channels). Osmosis provides the primary means by which water is transported into and out of cells. The turgor pressure of a cell is largely maintained by osmosis across the cell membrane between the cell interior and its relatively hypotonic environment.