An illustrator's life is always an adventure. Adventure because he/she works on a fascinating field, which gives pleasure for creating. Adventures because every day is different, and because all the projects vary constantly: not only the topics, but also the techniques, the media, etc. Un day you can work on an illustrated album, another on graphic humour for the press, and another on graphic novel, posters, or multimedia material. You have to be ready for changes, to change your perspective, to think of different addressees, and to adapt yourself to the different demands.

It is also an adventure because it is not only a question of creating new materials and works. It is also important to go to editors, to institutions, even to printing houses. And besides, there is the difussion task: talks, workshops, encouters with other professionals, book presentations, organization of exhibitions, etc.

THE CREATION OF ONE WORK

ONE EXAMPLE : "O NENO QUE TIÑA MEDO DOS ROBOTS / O ROBOT QUE TIÑA MEDO DOS NENOS"

EDEBÉ-RODEIRA

The creation of this book starts with the encounter of two authors, the writer (Miguel Vázquez Freire) and the illustrator (Xosé Tomás). After an idea from the writer, they two talk. The story of a boy who is afraid of robots, and another about a robot who is afraid of children.

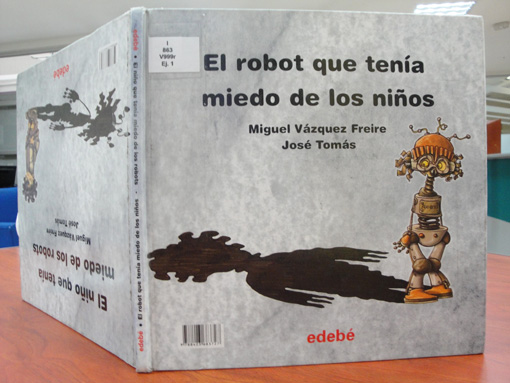

Two stories in one book. And the crazy idea of making two covers, and two stories which start at the beginning and finish...in the middle.

Time to start work! Both decide that the story is going to be one of parallelysms, to melt idea and form: the boy and the robot have got the same fears. And both share similar lives: they have breakfast, have a shower, listen to their parents, receive all their fears, go out to the street, get scared, they see each other come and...they meet. They need to make technical and graphic decisions. one half is read from one side, and the other from the other side. How to make a central image, common to both stories, which may be read from both sides?

There is a discussion between both creators, and finally comes the solution: a scene from above. Thus, the final illustration can be read in any direction, turning the book round, from left to right, from right to left, from top to bottom and vice versa.

Once this decision is made (a crucial, definite decision for the book), they start creating a world arround the characters.

The text talks about streets, houses, of a world where robots and humans live together, but no more details are expressed. The illustrator, following the theory of creative overflowings, is now the one in charge of filling all the gaps, and creating a visual identity for the book.

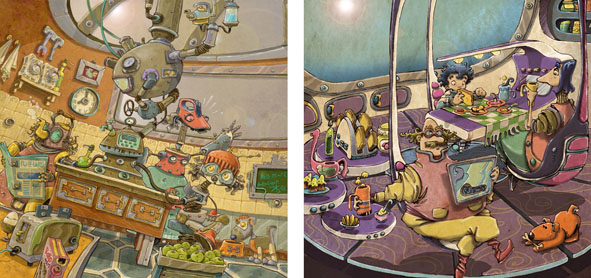

Then there comes a reflexion, based on the idea of contraries who are not so different: the boy and the robot.

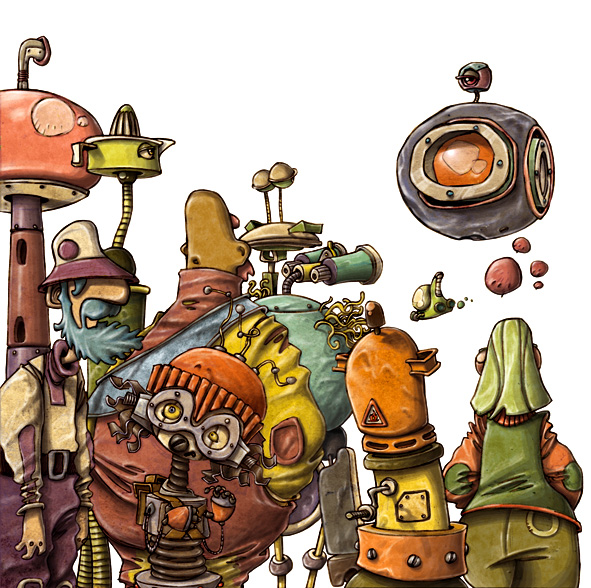

With the intention of bringing the protagonists together, the creators invent a future world, or even more, futuristic. In this world robots have reached the same intellectual and (very important) emotional level of humans. And humans have reached a high standard of technological sophistications. it was necessary to create an identity to robots, a kind of global aspect, and the conclusion was that they had to made of waste materials. This decision gave robots a "familiar" aspect: they were robots, yes, but they were made of elements we all know, which are part of our lives: hairdryers, vacuum cleaners, coffee pots, gas dispenders, washing machines, etc. Robots are "humanized".

Humans, on the contrary, are at an excessively technocratic stage. The boy, Luisiño, when he goes to the toilet, he does even touch the floor, because that tool where he sits is floating over the floor. Human houses are cold, technological, too perfect, just the opposite of the robotic imperfections.

Robots, then are humanized, and humans are robotized. They are not so similar. And their fears, therefore, are absurd.

And for some time the illustrator was looking for ideas for those "familiar" devices, to build all the robot gallery of characters.

The robot's kitchen is full of re-used devices: a diskette-toaster, a box of cereals with screws, tin apples, etc. The human kitchen is floating: the elements levitate over the table and the floor. And the dog humans have is robotic, less expressive than the one robots have.

Both authors want to create two universes which touch each other, in spite of the differences. And they want to express that prejudices against different people last for centuries: both humans and robots have false fears to each other.

Once the book is thought, the next step is to find an editor who relies on it, even though it is a risky project. In this ocassión, it was EDEBÉ-RODEIRA who did it, and decided to edit it in Spanish and Galician, to sell it everywhere in Spain.

THE DIFUSION

OF THE WORK

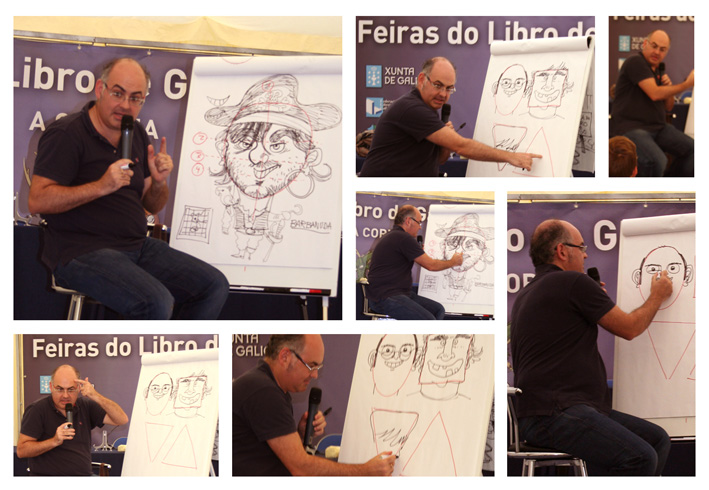

Illustrators do not only create a work from the solitude of their studio. Besides, they go out to the street, to schools, universities, libraries, and they talk about their work. In the case of this book, both authors organized workshops and speeches arround it, they showes how the book was made, and they even used audiovisual elements to create atmospheres while that was happening.

Workshops are an excelletn means so that readers may know the books, their types, their parts, their history.

With practical exercises, creative games and a long number of practice, they realise how important it is to communicate with images, a language that educational systems do not usually pay attention to.

Visits to mass media is also part of an illustrator work: sometimes to promote works which have been released, some others to take part in talks or interviews about the illustration profession.

To take part in the media (press, radio, internet, TV) is essential to show what society, sometimes, does not know deeply. It is crucial to speak about illustration, about its communication effects, about the importance of image, sometimes even above the word.

Below we can have a look at two videos explaining about the creation process of visual works, as well as about the illustration profession:

INTERVIEW TO AN ILLUSTRATOR: DANI PADRÓN

His creative secrets, his reflexions, his everyday life in a profession which is as hard as estimulating.

Dani Padrón (Ourense, 1983)

http://daniipadron.blogspot.com.es

Architect at ETSA

da Coruña. He landed in illustration through caricature and comic,

after winning an accesit at the IX Concurso Galego de Caricaturistas Noveis

(2009) and a second award at the XIV Certame de Cómic de Cangas

(2010). He started as an illustrator in 2011 with the Pura e Dora Vázquez

award (2011). In 2014, the Galician Editing Association gave him the Isaac

Díaz Pardo award for Pan de millo (by Migallas Teatro, edited byr

Kalandraka). And that book was chosen in 2015 for the Bratislava Biennal.

How long have you been working professionally as an illustrator?

The first book I made came out in 2011, and I made two more in the next two years. Living on this... less time. I would say I'm on my third year.

I was lucky I liked it very much, and I went on drawing just when all the other kids give up doing it. Later on, it became a tool to make toys. Many of the puppets I had were drawn by me.

Was there any teacher who helped you go on as a visual creator?

I had a teacher at school, Manolo Lorenzo, who always encouraged me to draw. He got involved in it all he could. it is true that the context was not the ideal one. At that time speaking about drawing was like a hobby, not a possible professional career, and then it was not common for students to think of working on it. But more recently, some years ago, professor Chema Mesía was someone essential for me, when I did my master in Education. He saw me grow as an illustrator and helped me a lot to give my first steps.

You are an important professional in the Galicia panorama. What does it mean for you to draw for children?

When I was a child, illustrations used to change a lot my perception of books. Sometimes because they were beautiful, some times because they were scary, or because they were imaginative, or even strange. Illustrate for kids is special because it allows me to live the same again, but now from the other side.

Could you describe your creation process with a writer when you make a book together?

The most habitual thing is that I receive a text from a publisher with a deadline to finish the illustrations. In these cases, I normally do the work without any exchange of opinions with the writer. I know that the ideal thing would be to work all together in the creation of the book, but that is not always possible. Sometimes asking for suggestions may end up bringing problems with time. Sometimes some writer got in touch with me to offer a project together. When this happens, we come to an agreement with a text, and I do my part during my free time. In these cases there is communication to create something which we both will be satisfied with. Sometimes I make two or three illustrations and then we try to find a publisher. And then there is the case of María Canosa.

Right. In the case of the writer María Canosa (you have made several books with her), how does the professional relation work when both creators know each other better and better?

With María everything is different, because it is no longer a professional relation. We are friends. No, in our projects together, we two participate in all the stages. We have enough confidence to criticise what we don't like from the other's work, and we are totally honest.

Do you remember any project which did not allow you to dream at night?

That happens to me in allprojects at the beginning. It is not for worry, but because when I have a new project I have it on my mind all day, especially when I amn not drawing.

When you face an illustrated album, what is you working process like? How do you organise your time? When and how do you move from the text to the images? Do you make many sketches? How do you decide the technique? Please tell us all those "secrets".

The first thing I do is read the text several times, and leave it to rest for one or two days, if it is not very urgent. During that time, as I said before, I think it over deeply, sometimes willingly and sometimes not. Unconsciously an idea is forming in my head of what I'm going to do, or what I think I'm going to to. Then I go straightly for the first illustration. Besides knowing the dimensions of the drawing,for me it is essential to place a text which lets me know the amount of paper I have to use for the image. In this first illustration I ususally try to put the main character(s) of the story, because that image will be a makr for the rest of the book. If the client doesn't mention it, I don't make a storyboard of all the book, and I don't make the illustrations in order. When I have an idea for an illustration, I do it, always trying ot make it fit what I have already done. And then one by one, until I finish the book.

Do you listen to music while you draw? Tell us a musician who has inspired you.

I like working with music, especially with film soundtracks. Not only for inspiration, but to feel company. I love James Newton Howard. But I change, I don't always listen to music. I also work with films or football matches.

Mention one or several illustrators that have inspired you.

David Pintor, Quentin Blake, Miguel Robledo, Tha, Gabriel Pacheco...

When you go to a bookshop to buy an illustrated albumn, what catches your attention?

I buy the books for two reasons: either because the illustrations attract me, or because I think they can hel me as a reference when I have to make my own ones, or even because I like the book as an object. In many ocassions the three factors coincide.

Thinking of new illustrators in Galicia, what would you say to all those who want to start professionally in this?

What I tell myself every day: if you are convinced that this is what you want, work as much as you can.

What is your opinion about the stimulation of creativity at schools in general?

I don't know if things have changes lately. When I studied, lessons were always the same, independently from the students' standard of creativity. I had some very creative friends experimenting academic failure, even though it wsa clear they had some special qualities. And no one did anything with them, nobody tried to potentiate their creativity. If someone was especialy good in some field, he had to follow the same path as the rest. They didn't talk of creativity, there were only good or bar marks.

Thanks a million,

master!